I’ve been talking about vibes a lot over the past week, so let’s talk about something a little more substantive. Trump and his movement basically have two main policy ideas: 1.) immigration restriction, and 2.) more tariffs. Let’s think about the second of these.

Tariffs aren’t just a Trump idea anymore – they’re now an important part of the Democratic policy toolkit. Biden’s tariffs on Chinese products, announced back in May, went well beyond anything Trump did in his first term.

I doubt a Harris administration would reverse this approach – some Democrats want to protect American jobs while others want to preserve American manufacturing capacity against the possibility of a war with China. So whoever wins in November, we’re probably going to see tariffs continue to be a key policy tool in the US.

Back in February, I wrote a post about why tariffs often aren’t as effective at reducing trade deficits as their proponents hope, link here.

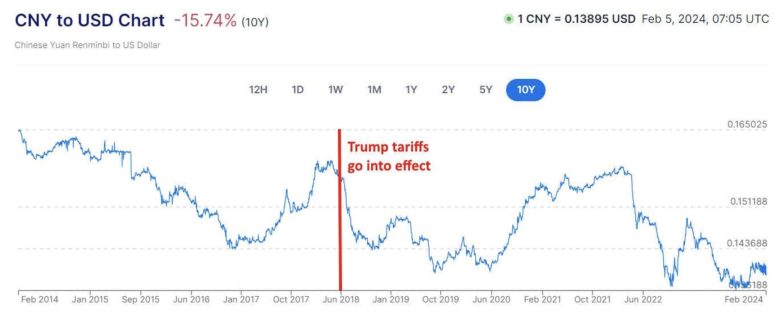

Basically, there are three reasons tariffs tend to be underwhelming. Most importantly, when you put up tariffs against another country’s goods, it causes that country’s currency to depreciate against your currency.

That makes your exports more expensive and makes imports cheaper for your consumers. This partially cancels out the intended effect of the tariffs. In fact, in the year and a half after Trump put tariffs on China in his first term, the Chinese currency depreciated significantly:

Another factor reducing tariffs’ effectiveness is the many ways that Chinese companies can get around them. They can “re-export” — basically, ship something to a third country, slap a “Made in Vietnam” or a “Made in Thailand” label on it, and then sell it to America, free of tariffs.

They can set up factories in third countries so that their products are actually made in those countries. They can sell parts and components to assemblers in third countries, in which case the US doesn’t even know they’re importing a bunch of Chinese goods.

They can take advantage of loopholes like the “de minimis” rule that allows China to sell small packages to America free of tariffs. And so on. All of these strategies can in theory be fixed with enough investment in data and monitoring. In practice they rarely are.

The third problem with tariffs is that they make intermediate goods – materials, parts, and components – more expensive for US manufacturers. Tariffs on steel and aluminum raise prices for American carmakers, aerospace companies, appliance makers, and so on.

Tariffs on batteries make it more expensive to build EVs in America. Tariffs on solar panels make it more expensive to produce energy for US manufacturing. And so on. This weakens US manufacturing and can hurt US exports.1

So between circumvention strategies, currency movements and damage to American manufacturers, Trump’s tariffs on China ended up reducing the trade deficit a lot less than their architects had hoped.

And although Biden’s tariffs are much higher – and Trump’s tariffs in a second term would likely be higher still – these factors will continue to exert an effect. This is not to claim that tariffs are ineffectual — they’re just a weaker policy tool than their proponents like to think.

Despite these inherent weaknesses, tariffs are still an important piece of the toolkit for preserving supply chains and defense manufacturing capacity against the possibility of a major war.

But it’s also possible that tariffs will have some unexpected benefits for people around the world — Chinese consumers who are getting a bad deal from the country’s current economic model, and developing countries that could benefit greatly from Chinese investment.

When we think about tariffs, we should think about these positive side effects as well.

Tariffs might help China to rethink its economic model

Zongyuan Zoe Liu has a widely read article in Foreign Affairs this week about the drawbacks of China’s manufacturing-focused economic model.

The article gives an excellent explanation of how China promotes manufacturing. Basically, it’s all about bank finance — banks loan huge amounts of money very cheaply to manufacturers, who then compete fiercely, resulting in a flood of cheap, often undifferentiated products.

These price wars result in collapsing profit margins, as all the Chinese manufacturers glut the market with products no one wants to buy. It also results in a flood of exports, as Chinese manufacturers try to sell their excess capacity overseas. And it results in a mountain of corporate debt, forcing Chinese companies to stay on the treadmill of unprofitable production just to keep making their interest payments.

What’s interesting is that this is very similar to how Japan promoted manufacturing from the 1950s through the 1980s. As Chalmers Johnson explains in his book “Miti and the Japanese Miracle”, a key component of Japanese industrial policy was “overloaning” to manufacturers, using a combination of public and private banks.

Japan found that if it promoted domestic overcapacity, it didn’t even need to promote exports much – they would just happen as a side effect of the domestic glut.

The big difference between Japan and China is that Japan’s government tried to balance out this overproduction with measures to raise prices, in order to save its private companies from becoming unprofitable. Cartels and other price-fixing measures – basically, antidotes to overcapacity – were one of the core features of Japan’s industrial policy.

China’s industrial policy, in contrast, leans in to overcapacity by dispensing absolutely massive government subsidies to manufacturers. This is why China’s overcapacity problem is much worse than Japan’s in the 20th century, which is why countries around the world are getting mad and putting up tariffs.

At the same time, China’s industrial policy is just exacerbating the price wars that are making its manufacturers unprofitable. It’s also hurting Chinese consumption — yes, there’s a glut of cheap products, but Chinese consumers can’t afford them because their employers had to cut their wages in order to sell more products so they could make their loan payments.

This system ought to change — creating an ocean of rusting metal and bankrupt companies helps no one. Interestingly, though, Liu thinks tariffs aren’t the solution. Instead, she thinks countries should encourage China to voluntarily restrict its exports and subsidize its manufacturers less:

A good place to start is by crafting more policies at the negotiation table, rather than merely imposing tariffs…China may also be more flexible in its trade policies than it appears. Since the escalation of the US-Chinese trade war, in 2018, Chinese scholars and officials have explored several policy options, including imposing voluntary export restrictions, revaluing the renminbi, promoting domestic consumption, expanding foreign direct investment, and investing in R & D…

Apart from voluntary export restrictions, Beijing has already tried several of these options to some extent. If the government also implemented voluntary export controls, it could kill several birds with one stone: such a move would reduce trade and potentially even political tensions with the United States; it would force mature sectors to consolidate and become more sustainable; and it would help shift manufacturing capacity overseas, to serve target markets directly.

But the keen-eyed reader will notice that Liu contradicts her own argument here. She notes that China began exploring voluntary export restrictions, currency appreciation, domestic consumption promotion, etc. only because Trump put up tariffs on Chinese goods. It stands to reason that if the US wants to get Chinese policymakers to consider these salutary options even harder, there needs to be some sort of penalty for not taking these steps.

In fact, earlier in her post, Liu lists tariffs as a big downside of China’s current overcapacity-promoting policies:

Since the mid-2010s, the problem has become a destabilizing force in international trade, as well. By creating a glut of supply in the global market for many goods, Chinese firms are pushing prices below the break-even point for producers in other countries. In December 2023, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen warned that excess Chinese production was causing “unsustainable” trade imbalances and accused Beijing of engaging in unfair trade practices by offloading ever-greater quantities of Chinese products onto the European market at cutthroat prices. In April, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned that China’s overinvestment in steel, electric vehicles, and many other goods was threatening to cause “economic dislocation” around the globe. “China is now simply too large for the rest of the world to absorb this enormous capacity,” Yellen said.

For the US and other countries to spontaneously and voluntarily remove the threat of tariffs would thus remove one of the major downsides of overcapacity. Trying to wheedle China into enacting voluntary export restrictions would be useless if China could simply ignore the wheedling and use the rest of the world as its dumping ground for excess capacity.

Yes, it would benefit the people of China if their government changed the country’s economic model to raise the living standards of ordinary consumers instead of encouraging unprofitable overproduction. But if benefitting the ordinary people of China was what the government cared about, they would have done it already.

China’s government thus needs an additional incentive to shift its economic model. That incentive is tariffs. By stopping China from being able to use the rest of the world as the release valve for its overproduction, the US and other countries can hasten the day of reckoning when Chinese companies find themselves unable to offload their products at any price. That reckoning will force the Chinese government to figure out how to cut back on production.

At that point, the US and other countries can offer to remove tariffs if China agrees to voluntary export restriction and currency appreciation. But without the “stick” of tariffs to force China to deal with its own overcapacity, nothing is likely to change.

Tariffs on China could speed up development across the Global South — and maybe even in the US

There’s another important way in which tariffs on China could help the rest of the world. One way for Chinese companies to partially avoid tariffs is to move their factories out of China to other countries, like Vietnam, Mexico, or Morocco.

This results in somewhat less revenue for China because the Chinese companies have to pay the labor, land, and energy costs in the country where they set up their factories. But Chinese companies still get to sell materials, parts, and components to their overseas assemblers, and they still get to keep the profits. So they get to partially avoid the impact of tariffs.

The US and other countries could close this partial loophole, if they really wanted to, by imposing tariffs on goods made by Chinese-owned companies instead of just on goods made in China. This would set up a cat-and-mouse game where Chinese companies would try to set up elaborate systems of shell companies and overseas partners to avoid detection by the tariff regime.

Ultimately, though, it would make it enough of a hassle for Chinese companies to sell things to America and other tariff countries that they might just give up and go looking for other markets.

But if the tariff countries don’t close this loophole – or close it only partially, e.g. by putting tariffs on Chinese-made components but not on Chinese brands – then it creates a huge incentive for Chinese companies to build factories overseas. In fact, as The Economist reports, this is already happening on a large scale:

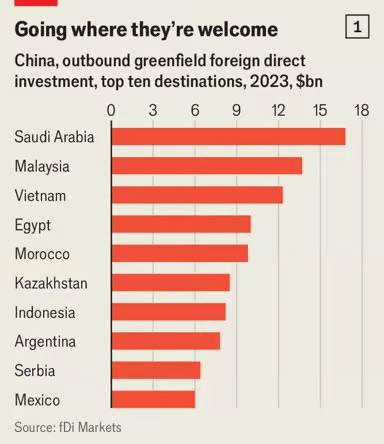

[China’s] greenfield FDI (building a new mine or factory, say, rather than buying one) surged to a record $162bn last year, up from $50bn a year before…Nearly three-quarters of that was in manufacturing…

Some Chinese firms are trying to skirt trade barriers by shifting production from China to other developing countries. That is an approach long taken by Chinese solar firms, which were, in effect, locked out of the American market in 2012 by anti-dumping duties. America imports almost no solar panels directly from China, but buys lots from South-East Asia, where Chinese firms like JinkoSolar, Trina Solar and Longi, the world’s three largest producers of solar modules, have built big factories…

That strategy is now being emulated in other industries, which explains Chinese firms’ surging investment in manufacturing abroad. Although some factories are being built in the West, the lion’s share of activity is in the global south, home to nine of China’s top ten destinations for greenfield FDI last year…In July BYD, a Chinese electric-vehicle company, opened a new car factory in Thailand, its first in South-East Asia. CATL, a Chinese battery firm, is expanding production in South-East Asia and reportedly exploring investments in Morocco and Turkey.

And here is The Economist’s chart of where the Chinese investment is going:

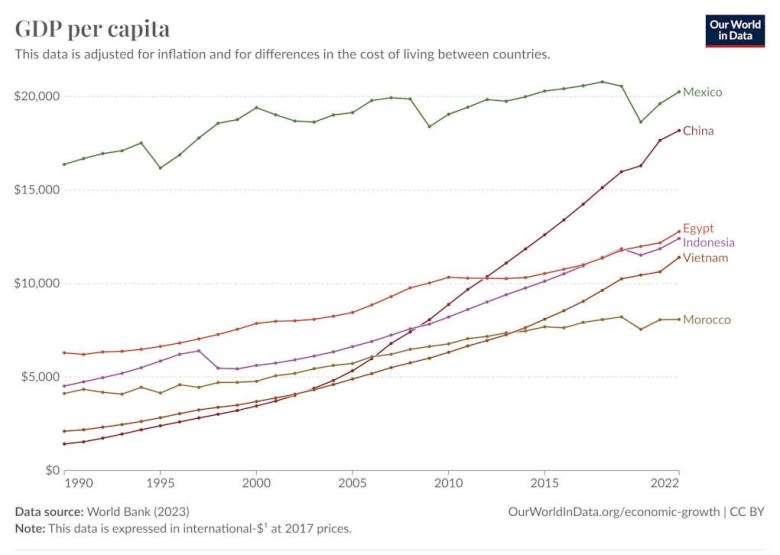

It’s difficult not to see this as a good thing. Leaving out Saudi Arabia and Kazakhstan — which are clearly just energy plays — the countries where China is investing are mostly quite a bit poorer than China.

Mexico is still slightly richer, but it’s stagnant.

In other words, these are all countries that could badly use Chinese manufacturing investment. China is becoming a mature economy, while Vietnam, Indonesia, Egypt, and Morocco still badly need the growth in living standards that foreign-owned factories help provide.

And it’s tariffs in the US and other countries that are making this happen. As The Economist notes, other reasons are pushing Chinese companies to build factories overseas – rising Chinese labor costs and slowing Chinese domestic demand – but tariffs are proving to be the decisive factor.

Many strong factors bias Chinese companies toward keeping their factories in China – lack of language barriers, ease of navigating local regulations, political pressure, and so on. Tariffs generate the key push to overcome this home bias and spread the wealth throughout the developing world.

Now, cynics might respond that Chinese companies will only move low-value assembly work to these other countries while hoarding high-value component manufacturing for themselves. Indeed, this is exactly what multinational companies did to China for many years!

As recently as the early 2010s, many Chinese factories were still stuck doing low-value assembly work on high-value components made in Korea, Taiwan, Japan, or the US, using machines made in Germany or Japan. It was only recently that China started doing more of the high-value component manufacturing, design, branding, and marketing.

But if China could climb up the value chain, then so can Vietnam, Indonesia, Morocco and Egypt. Over time, the companies in these countries that do assembly for China will learn enough of the tricks of the trade that they’re able to make more and more of the harder, more valuable stuff.

The US and other tariff countries can help accelerate that process. By putting tariffs on Chinese components, but not on Chinese brands, they can incentivize Chinese companies to move more of their high-value work to poorer countries in Asia, the Middle East and Latin America. Companies like BYD will then be able to circumvent tariffs, but only if they transfer their technology to developing countries.

In other words, tariffs by the US, Europe, and others might help usher in the next phase of globalization. They’re a costly inefficient policy that sometimes backfires but that might be an acceptable price to pay for smashing the unsustainable, toxic pattern of China-centric globalization that prevailed in the 2000s and 2010s.

1 Of course, you can get around this problem by only putting tariffs finished consumer goods, like cars or appliances. But the problem is that intermediate goods are most of what China sells to the U.S., and since one primary goal of tariffs is to secure US supply chains against a possible war, then tariffs on intermediate goods are unfortunately necessary.

This article was first published on Noah Smith’s Noahpinion Substack and is republished with kind permission. Read the original here and become a Noahopinion subscriber here.